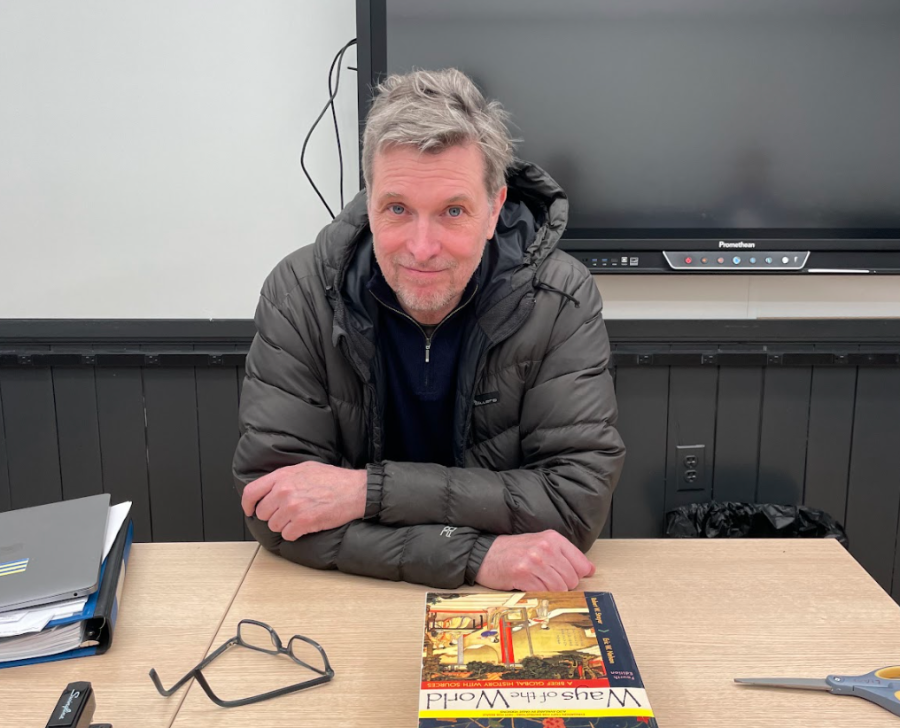

Lambert Gingras: How Trust in Life’s Path Brought Him to Dyker Heights

May 10, 2023

“At some point, I realized that I would not go back,” said Lambert Gingras, reflecting on the decision that steered the course of his life in a direction far off course from where it seemed headed. While the path he took was one filled with love, growth, and adaptation, nothing in Gingras’ background would lead one to believe that he would later be a history teacher at Poly Prep Country Day School. This year has been his first at Poly.

Gingras was born and grew up on the south shore of Montreal. He got his B.A. in philosophy and then worked as a reporter for two years at the Montreal Daily newspaper. He then got a master’s in political science in Quebec City, to then later return to Montreal and attend one year of graduate school at McGill University. Gingras then attended Cornell University for a Ph.D.

Although Gingras never finished studying for his Ph.D, that pursuit brought him to New York, where he met his wife, Nicole. Gingras’s time as a student in the United States was one of exploration. “I was like a tourist mostly,” he said. Eventually, New York began to feel like home for Gingras and he began to consider himself a New Yorker.

Critical to his decision to move to New York is something you wouldn’t find in his long list of credentials — his trust in where life takes him. “You know, sometimes life decides for you,” Gingras said with a shoulder shrug. Moving to the United States was a “gradual decision” for Gingras.

It took Gingras 20 years to apply for citizenship in the U.S., and ultimately it was his wife, his work in the U.S., and the prospect of starting a family that kept Gingras tied to the life he was building in America.

“There were a bunch of people that must have been there, a hundred people being sworn in the same day and people from all over the world…it was really cool,” Gingras smiles as he recalls the day of his swearing-in ceremony as a new American citizen. “It was really from all over the world,” he adds.

When deciding to seek citizenship, Gingaras had to, maybe for the first time, trust where life had taken him, rather than trust in the next adventure. “When you take citizenship, you sort of make an official break. You have to admit to yourself, this is for good. This is not temporary,” he said.

Mr. Gingras’ two identities as an American citizen and native Canadian rather blend than intersect. “Montreal is within 30 miles of the American border,” he notes. “We shouldn’t overstate the differences.”

Another reason why Gingras held off on getting citizenship is because “citizenship doesn’t necessarily give you that much,” said Gingras casually as his blue eyes scanned the room. Around 9.2 million immigrants in the United States are eligible for U.S. citizenship, but less than 1 million apply each year, according to the Boundless 2022 State Of New American Citizenship Report. Rather, Gingaras implies that citizenship here is more about what you put in, and what you choose to take out. American citizenship is about the commitment to American life and culture, something he has now fully embraced.

Deciding to get citizenship was one of many decisions that shapes Gingras’ life today. Among those is his decision to become a history teacher. “After a while I got bored, and I wanted to do something else,” he says, reflecting on his life in New York after going to Cornell. He was a French teacher for six years before he decided that his future would be in the history field. This was yet another decision that Gingras gradually made.

“I’ve always liked the written word and thinking about problems and reading about various hypotheses, about problems, about social issues and political problems, and what’s been done in the past to deal with some of those problems,” said Gingras.

Gingras used the same philosophy in deciding to stay in the United States and in deciding to be a history teacher: trusting life and following his heart. His heart told him to follow his wife and education to the United States, and to follow his passion for history all the way to Poly Prep Country Day School’s history department.

While Gingras believes that being an immigrant has played a less important role in his experience as a history teacher, he represents a statistic that disproves the claim of diversity in the educational system. According to George Mason University Institute for Immigration Research, “While immigrants comprise 13 percent of the U.S. population, they make up only 11 percent of all teachers.”

“I don’t think there are many countries in the world where a foreigner could teach the nation’s history,” said Gingras with a beaming smile.

“It’s such an international place that having a foreign citizen teach the history of the United States doesn’t seem strange at all. That’s just the way that we do things here as Americans, you know?” he adds.

Jasper Whiteley, a sophomore at Poly Prep, was a student in Gingras 20th Century World History course this year. Jasper grew up in Canberra, Australia, then lived in London for two years, and moved to the United States seven years ago while in the fourth grade.

“One’s interpretation of history in school is sometimes affected by the political and social norms from where they come from,” said Whiteley, “Sometimes I can understand some of the foreign political policies that we might be looking at throughout classes as maybe Australia’s own political policy mirrors them.”

Speaking to Gingras’s effect as a teacher, Whiteley notes, “He was able to get a good aptitude for the levels students were at,” and “he [Mr. Gingras] brought a realm of current-day politics into the classroom.”

AJ Blandford, a middle and upper history teacher at Poly Prep, comments on their time working alongside Gingras. “He’s only been here for a couple of months, but it’s been really great,” quickly adding, “He always wants to talk about politics.”

Blanford worked with Gingras this year on group work and projects, which they say was “sort of new for him.” However, Gingras met this task with enthusiasm and dedication. “He was like, okay, like I want to try this,” Blandford said.

Gingras does believe that “Most foreigners in my position at least probably know a lot more about the United States than Americans would know about other countries.” His background has made him a better teacher in a sense, forcing him to learn things about the United States that people born here would not consider — for example, health care and gun accessibility.

“Where I grew up, you didn’t have to worry about health care. You don’t have to wonder, do they have a health care plan? Will I lose my health care if I lose my job?” he said. This outside perspective on a part of American life has been invaluable as a discussion point for Poly students.

Gingras remains shocked, too, by the lack of gun safety in the United States, especially as compared to that of Canada. “The gun situation is just awful. I think a lot of Americans would agree with that,” said Gingras with a sigh. Gingras’s perspective on these political differences has enriched the learning of many Poly students.

“I feel like I’m in the right place,” said Gingras.