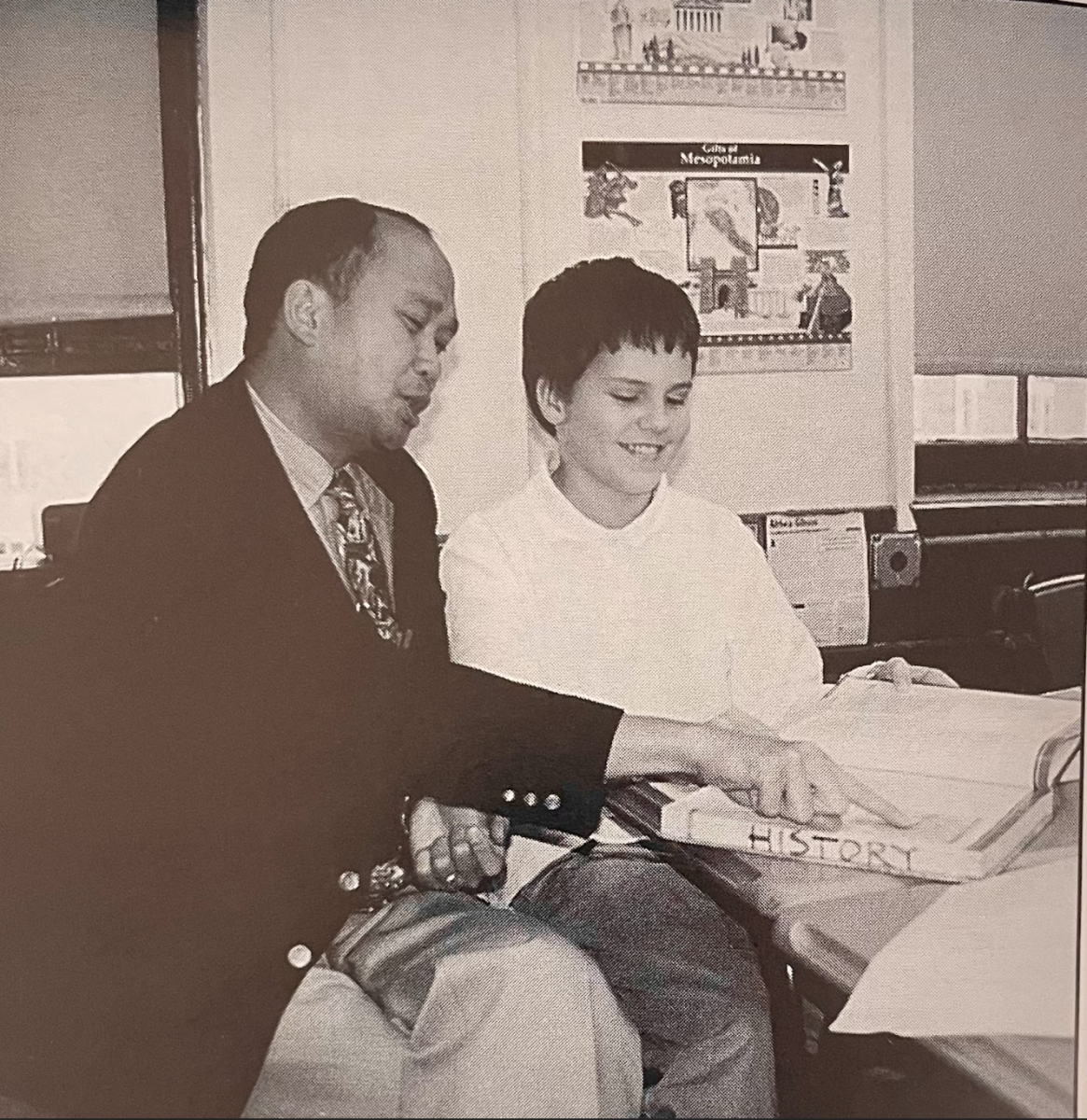

Back to her hometown roots, Phoebe Aberlin-Ruiz sits in her office in Brooklyn, New York. In her classroom, which doubles as her office, Aberlin spends her time teaching students during their Health class block. The class is in room 221, with white desks and royal blue chairs. Aberlin’s chair is the only different one, with wheels on the bottom, a dark grey coloring, and the ability to spin in circles. In that chair, she teaches students from all grades at Poly how to be ‘better humans.’ Upon first glance, it’s a normal classroom where one would never expect such meaningful memories, with both Aberlin and other students, along with lifelong lessons to be created. But it’s here where she teaches students from all grades at Poly how to be “better humans.”

Being a “better human” to Aberlin does not mean being a smarter, funnier, or even “kinder” person. Instead, it means having more respect and understanding of basic human rights. Although these seem like simple things, Aberlin has had her fair share of experiences with people who don’t seem able to wrap their heads around them. Before joining Poly’s community, Aberlin worked at a Rape Crisis Hotline in Bergen County, New Jersey: a job that not many people in the world can maintain healthily in. Most let their mental health deteriorate because of the mental stress and pressure that comes with this job, but because of Aberlin’s resilience and understanding of her mental health, Aberlin is one of the few who were able to keep going. These experiences have forced Aberlin to have the want, or the need to “create better humans,” said Aberlin.

Phoebe Aberlin-Ruiz is a name that carries so much weight. Just by looking at her, you can already tell she’s a kind person. Her black hair is pulled back into a tight bun, sitting just below the top of her head. Typically, her face is usually forced into a stern look, but her brown eyes give her entire endearing, yet bold personality away.

Aberlin grew up going to Saint Ann’s School in Brooklyn and then went on to major in Gender Studies in California at Occidental College. Fresh out of college, all Aberlin wanted was to “find a job that was near where [her] boyfriend lived.” She quickly found an add in the newspaper back in New Jersey for a spot at a rape crisis hotline. Stepping into the office, she wasn’t quite sure what to expect besides the fact that her job was to answer phone calls for the hotline and assist the clients. However, for her first four months there, Aberlin was never once the head of any case. She would stick with those clients for months at a time, guiding them through court till the majority of their case was over. This long process was her training. Little did Aberlin know that even with all this training, nothing would truly prepare her for her first, real, case of her own.

Aberlin’s first case put her in a position full of doubt about her skills, her choice of job, and most importantly, whether she would be able to give her client justice. “No matter how many times [I] trained, [my] first time out by [myself was] the most terrifying thing in the world,” recalled Aberlin. Thankfully, those four long months of training kicked in almost immediately, and she was able to get her nerves together and help her client in need. After that case, Aberlin then went on to work on many cases over the next two and a half years.

Since this job wasn’t one that many were interested in, or qualified for, the rape crisis hotline consisted of a small, but serious and dedicated community. There were typically six people in total who worked there, according to Aberlin. The turnover rate was high, and usually members only worked there for a year and a half. This center is one of the “approximately 1,200 RCCs in [the U.S.],” according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, RCC standing for Rape Crisis Center.

During her time, she never truly had a problem with her job: she loved helping people, and this was something she was passionate about. It wasn’t until late in her two and a half years there that she realized this job wasn’t going to last her forever.

The case that changed her the most began at three in the morning. Aberlin glanced out her window, and the dark night allowed no light to shine through it. Her heart beat fast, speeding up more every once in a while, as she tightly gripped the hotline phone in her hands. Next to her, she had another phone, her personal phone, dialed to the police in Bergen County. Across from her, she had her house phone dialed to the suicide crisis hotline.

Though it was early, Aberlin knew she had no choice but to stay up in the hopes that she would save a woman’s life. Aberlin was trying to stay quiet so as not to wake her boyfriend. The woman on the phone was also trying to stay quiet. Just down the hall, the woman’s sixteen-year-old daughter lay in her room, asleep and unaware of the struggles her mother was going through. In her hands, the mother held two bottles of pills, threatening to take them both, with the intention of ending her life. She had recently been sexually assaulted, and it was Aberlin’s job to be the one who provided her with support. Aberlin’s mind was filled with dread, only slightly lowering as relief swept in when the woman dumped one of the pill bottles into the toilet and let it flush.

The next bottle of pills was soon emptied too. However, not into the toilet, but swallowed down the woman’s throat.

As Aberlin’s stomach began to sink in horror, the police informed her that they had arrived and promptly hung up. Aberlin hung up the other two phones, saw it was already five in the morning, and began to get ready for her day, knowing that she wouldn’t be able to sleep. However, whilst she prepared for her day, there was one prominent thought coursing through her head. “What am I doing? I cannot sustain this,” thought Aberlin. It was just “soul-crushing on a regular basis,” said Aberlin, shaking her head. She knew her mental health was at serious risk if she continued.

Understanding that, she was able to realize that a change was needed. The next day, she began to search for a new place to work. Just like when she was fresh out of college, Aberlin needed a job. “I was going to work retail, I didn’t really care at that point,” said Aberlin. All she wanted was out.

Although she knew she loved teaching from giving presentations to schools about sexual assault during her time at the hotline, and wanted to continue it, unless a job popped out at her, she wasn’t going to endlessly search for a job as a teacher. Luckily for her, a teaching job did pop out right at her. “I had come to Poly to do an Upper School Assembly about sexual abuse, and they were expanding the health program,” said Aberlin. She laughed as she continued, thinking fondly of her beginning at Poly, “and that’s sort of how it all started.”

Once she began working at Poly she noticed little things that would trigger her into action, just like at the rape crisis hotline. “Something that sounds like my old pager, I get up and start to get ready, 22 years later,” admitted Aberlin. “It’s so ingrained in my brain because you had to be on in 20 seconds.” Being exposed to traumatic events, even indirectly, can negatively influence one’s life, according to the Administration for Children and Families. And although small sounds slightly affect her and remind her of her time at the hotline, Aberlin is one of the lucky few who do not have severe post-traumatic stress disorder from working a job like hers. “I learned a lot about the human psyche, but also how resilient people can be and come back from some of the most atrocious and horrible things if they’re given the support and the tools that they need,” said Aberlin, staring into the distance. And although she believes the human psyche is amazing, she also believes that no one should have to recover from assault, which is what created her goal to “create better humans,” something she takes pride in teaching here at Poly.

Aberlin has worked at Poly since 2002, dedicating her work to teaching her students how to prioritize their mental health and create a better world with better people. Aberlin is positive that her job is forever unfinished, while others are sure that she has already taught mass amounts of students to live as a part of a better society. “[Aberlin’s] teaching style was always evolving and was very engaging, effective, and relevant,” said Aimee McLoughlin, a former health teacher at Poly. “[Aberlin] is very supportive, caring, and dynamic, which always showed in her teaching.” Many of her qualities as a health teacher stem from her former job, which taught her skills beyond helping others in times of need.

Now, she looks back on her days in the past fondly, proud of the work she did. “I was 21 and kind of dumb and [I] didn’t realize what I was getting into,” revealed Aberlin. As she spoke, a small smile came across her face, and she relaxed back into her chair. However, it was also the most defining part of her early life and career. “I do not regret a minute of that job. Ultimately, I wish it were a job that didn’t actually have to exist, but I’m glad it does for the people that need it.”