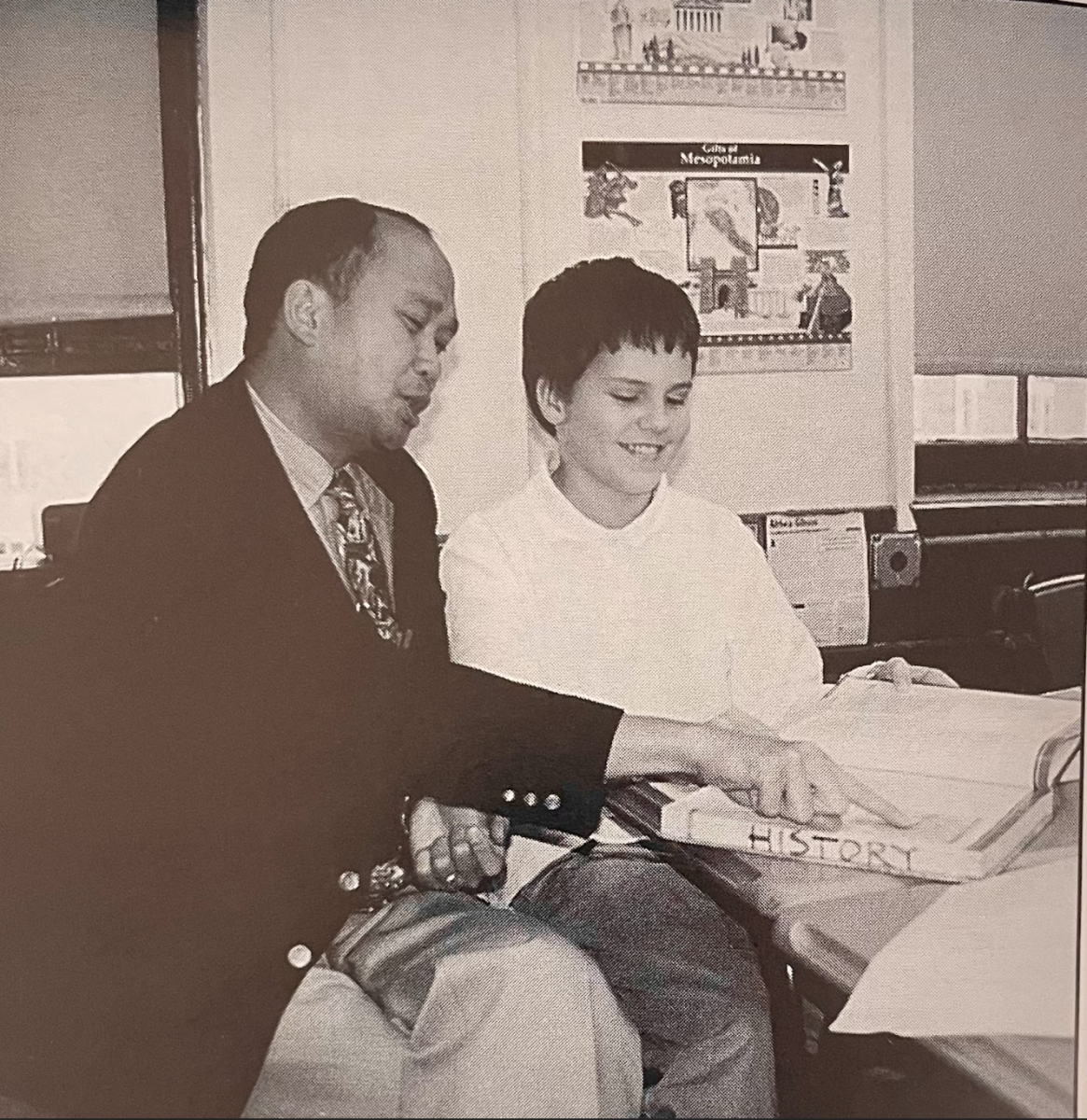

On the morning of Wednesday, September 12, 2001, Middle School History Teacher Caesar Fabella boarded the Q train to Manhattan with six Poly Prep students hand-in-hand. The students alongside Fabella made their way to 42 Street in Times Square as they awaited the various reunions the students would have with families. Riding over the Manhattan bridge, “we saw all the destruction and the devastation…I just started crying,” admitted Fabella, who is still a beloved history teacher at Poly in 2025. It was then that it all became very real. Finally, the train pulled into the station on 42 Street. After some of the scariest hours of their lives, the six students reunited with their families and Fabella took the train back to Brooklyn to return home.

The tragic experience of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack caused many Poly faculty members to expand beyond the role of a teacher, and serve as families and provide homes for numerous students. Among the chaos and unknown, many Poly students who commuted from Manhattan had no way home. As a result, during his first year at Poly, Fabella took in six of these students as his own children, giving them more than just a place to stay during this horrific event.

At 8:45 a.m. on Tuesday, September 11, 2001––which marked the school’s second full day of classes––Poly Upper School students gathered in the Memorial Chapel for a daily assembly. The Middle School students, however, were stationed in the Richard Perry Theater. The weather was calm, like a typical early September morning. The sky was particularly free of clouds and projected a bright shade of blue. “It was a beautiful day,” described Fabella. In the school building, loud voices of enthusiasm and anticipation for a new year of classes filled each room.

The beginning of the Upper School assembly flowed through normal rituals and consisted of back to school traditions such as speeches from the senior class president. In the midst of the senior’s speech, Headmaster David Harman rose from his seat in the chapel and fearfully announced one of the scariest facts the Poly community would ever hear. “I have just been informed that a plane has hit one of the Twin Towers,” he said. In shock of what had been said, the room instantly became silent. “At first I remember thinking, [what a] crazy accident,” said History Teacher Harold Bernieri and former seventh-grade dean. Believing this plane crash had been a horrific accident, at 9:15 a.m. faculty members sent all Upper School students to their first period classes.

As this day marked Fabella’s second day of teaching Middle School history, he spent the morning in the theater instead of the chapel. No word was mentioned about the tragedy to the Middle Schoolers, until after the assembly. At 9:15 a.m. Fabella began his sixth-grade history class in room 207A. Only minutes into the class, Middle School Dean Larry Patton came by Fabella’s classroom to deliver the same heartbreaking news that was delivered at the Upper School assembly. However, when he came back several minutes later, it was clear that this event was more than an awful accident. Patton returned, “with a grim face, and he said a second plane hit the towers,” and told everyone to remain in their designated classrooms, revealed Fabella.

Immediate feelings of terror and confusion rushed throughout the sixth-grade classroom. Many wondered where their parents were or if they would be able to get home. “The atmosphere around the hallways was grim,” wrote Poly Alumni Joseph Gallina in the October 2001 edition of the Polygon. Very few children truly understood the situation, and the ones that did, were horrified. During this time many students felt as though “[there were] no magical words that anyone [could] say to make everything better,” wrote Nandita Kripanidhi in the October 2001 edition of the Polygon. As a result, various faculty members began comforting children, while trying their best to organize the chaos. “Students were still desperately trying to reach their loved ones in Manhattan. Some of them [were unable.] It was at this point that we saw the best of Poly,” wrote Gallina. Different faculty members rushed through the hallways and into classrooms attempting to find some sort of solution to the crisis, one of which was Patti Tycenski, former seventh-grade dean. Tycenski “emerged as a beacon of reassurance,” mentioned Fabella, in his 2024 Spirit Award Acceptance Speech. “With only two semi-working phones in her office, she moved from room to room, helping students living in Lower Manhattan and Brooklyn contact their parents to let them know they were safe.”

Tycenski’s determination to comfort and help the Poly community motivated Fabella to do the same. “In retrospect I think I was inspired by what [Tycenski] selflessly did,” he mentioned. Fabella quickly brainstormed ways to help the situation, knowing that he would do everything possible to do so. “I said to myself, what can I do?” Fabella instantly thought of the Poly students that lived in Manhattan and correctly assumed that they would not have a way home. Prior to teaching at Poly, Fabella taught at an all boys school on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, Allen-Stevenson. Fabella knew that many of his former students from the Allen-Stevenson school, now attending Poly, in particular, would need a place to spend the night. Since most of them lived on the Upper East Side, these students would not be able to reach home until at the earliest, the following morning. “I spread the word around… I told [students to tell any Allen-Stevenson boys] that [I would] take them in to spend the night,” mentioned Fabella. Six students showed up to Fabella’s classroom, two of whom were brothers, Jordan and Dustin Tupper. Being in eighth and tenth grade, the Tupper brothers were young teenagers at the time. The four other young boys, Eli Rousso, Alex Melnitzky, Ace Cronstein, along with one last student who remains unidentifiable, were in different grades across high school during that year. Jordan Tupper used Tycenski’s phone to contact his father who tried to make sleeping arrangements for the two children. “He tried to call our grandma [to ask if we could spend the night]…but we couldn’t get there. So we were stuck,” revealed Jordan Tupper. Dustin Tupper was especially relieved when Fabella offered any Allen-Stevenson boys to spend the night because he did not want to split up from his older brother. “We could have [stayed] with friends, but [my brother and I also could have] decided to go with different friends, and [that was] the type of day where we certainly did not want to be split up,” said Dustin Tupper.

After gathering together, the group of six children plus Fabella waited until around 6:00 p.m. to depart from Poly and drive to Fabella’s home. Since Fabella does not know how to drive, he had to coordinate other arrangements for the children to arrive at his house safely. Robert Aberlin, who used to work at Poly and is now a member of the Board of Trustees, offered to drive the group back to Fabella’s house. “[It] took him three hours” to arrive at Fabella’s house because of how slowly everyone had to drive, revealed Health and Well-being Faculty Member Phoebe Aberlin-Ruiz, daughter of Robert Aberlin. Driving through Brooklyn was the students’ and Fabella’s first glimpse into the tragedy other than the horrific clips they managed to watch on the school televisions. “[You could] see tiny showers of paper and stuff,” shared Fabella.

Upon arriving at Fabella’s house, the children gathered around the single television, watching the news in an attempt to understand the current events. The news channels showed the terrors of the attack and the devastating collapse of the two buildings. “There was the actual unfathomable realization of a gaping, flaming hole in [the] first one of the tall towers, and then the same thing all over again in its twin,” according to a New York Times article published on September 12, 2001. After spending the entire day trying to grasp the recent news, the boys wanted to know what had happened. “I remember [Fabella] clearly turning [the television] off when it got pretty dark,” added Jordan Tupper. Fabella provided them with a lot more than food and a place to sleep though. “He treated us just like we were part of his family. He made us feel safe on a day where we had no idea really what was going on,” said Jordan Tupper. When the children got ready to go to sleep, feelings of terror, uncertainty and anxiety kept them awake. Some children slept on a pull out couch, while others laid on the floor tossing and turning aimlessly. “[Fabella] was constantly checking on all of us to make sure we were okay, making sure we had what we needed. I remember not sleeping at all,” continued Jordan Tupper.

The next morning, Fabella along with the six boys embarked on their journey to Times Square, where the children would reunite with their families. Since the Q train travels over the Manhattan bridge, they could see the horrifying aftermath of the attack, “but [Fabella] was just there with us. It was nice to have a friendly face and an adult who was making us feel like everything was going to be okay,” noted Jordan Tupper. When Fabella and the boys arrived at Times Square, the families thanked Fabella for his kind gesture. “[They] were immensely grateful,” added Dustin Tupper. But Fabella never thought twice about supporting the Poly community in this way. He felt that “[he was] just doing the least that [he could]” to help the situation. Kate Flahive, former Middle School math teacher at Poly and good friend of Fabella, recognized his kind heart and added that she never doubted that he would do something like that. “That’s just who Fabella is,” commented Flahive.

Fabella took the same route back to his home, but this time without the six boys. Riding the Q train over the bridge, “I [saw]… the devastation, that it’s like a pillar of dust [for the second time]. It is something that is going to be etched in my mind for the rest of my life,” added Fabella. Fabella disembarked the train at his regular station in Brooklyn and walked over to his house where his wife and son were waiting for him. “[I] hugged my wife and my son… [and] we just spent the rest of the day together,” concluded Fabella.

Twenty-three years later, Fabella received the Poly Prep Spirit Award. This award goes to a faculty member who embodies the core values of Poly and is an active member of the community. Fabella continues to have a positive impact on the Poly community through engaging Middle School history classes and events such as “Fabella Fridays” where he treats his students with cookies and candy. During the award ceremony, four of the boys visited the Poly campus, giving Fabella the opportunity to reconnect with them as grown adults. Some of the boys have children and families, but they, too, still remember this day very vividly. “It’s kind of funny, because afterwards, not that much changed…except [I knew] these were people [I could] count on if [I]needed to,” said Dustin Tupper. The Poly community has remembered the events of 9/11 every year to this day, and gathering at the memorial is also a time for faculty members who experienced overlapping narratives, to recount these experiences. “When I see [Aberlin on the day of 9/11 remembrance] we just nod at each other and say, [I] remember that day pretty well,” added Fabella.

Editor’s Note: While writing this story, I came across one large issue with identifying the name of the last student who stayed the night at Fabella’s house. Neither Fabella nor the two students whom I was able to get in touch with remembered the child’s name. Every source confirmed that six students were present at Fabella’s house, however, it was difficult for them to remember his name since the students were in different grades at the time, and Fabella was his teacher many years ago at the Allen-Stevenson school. This is a critical part of the story and limited my ability to highlight other individual narratives. Additionally, I was unable to retrieve the contact information for the other three students who I was able to identify, even after speaking to numerous faculty members. In order to address this, I focused on the two students whom I interviewed over Zoom, and refrained from mentioning too much about the other four students in order to avoid mis-representing their opinions or narratives.