The Poly Prep administration, with help from student groups and faculty committees, has introduced a more straightforward approach to the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the classroom for the new year—calling it “Stop, Slow, Go.” The three-tier system, which categorizes assignments based on AI permissibility, is designed to balance innovation with academic integrity.

Under the new framework, “Stop” marks assignments where AI is completely banned, “Slow” allows limited use with teacher approval and “Go” fully permits it with proper communication and citation. The policy represents a shift from last year’s loosely defined guidelines, which left many students uncertain about when AI tools like ChatGPT could be used.

Assistant Head of School and Head of Academics, Michal Hershkovitz, explained that the goal is to help students learn responsibly and not to replace their own thinking. “You have got to write those papers that drive you crazy,” she said. “You have got to do the hard thinking that makes your head ache. There is no shortcut to becoming an educated person.”

Each department has interpreted the framework differently, depending on the nature of its coursework.

In Poly’s English and history departments, most assignments fall under “Stop” or “Slow.” Teachers have reduced take-home essays in favor of in-class writing, projects and oral assessments to ensure students’ ideas remain their own. “AI is accelerating a process that was already taking place—rethinking what kinds of assessments best demonstrate student knowledge and skills,” said Virginia Dillon, the chair of the history department.

English Department Chair Peter Nowakoski emphasized that the policy is less about restriction and more about adaptation. “As educators, we want to be forward thinking and [keeping] things like, ‘how do we help our students best?’ [in mind],” he said. Rather than restricting AI, teachers are exploring how to use it to deepen students’ learning.

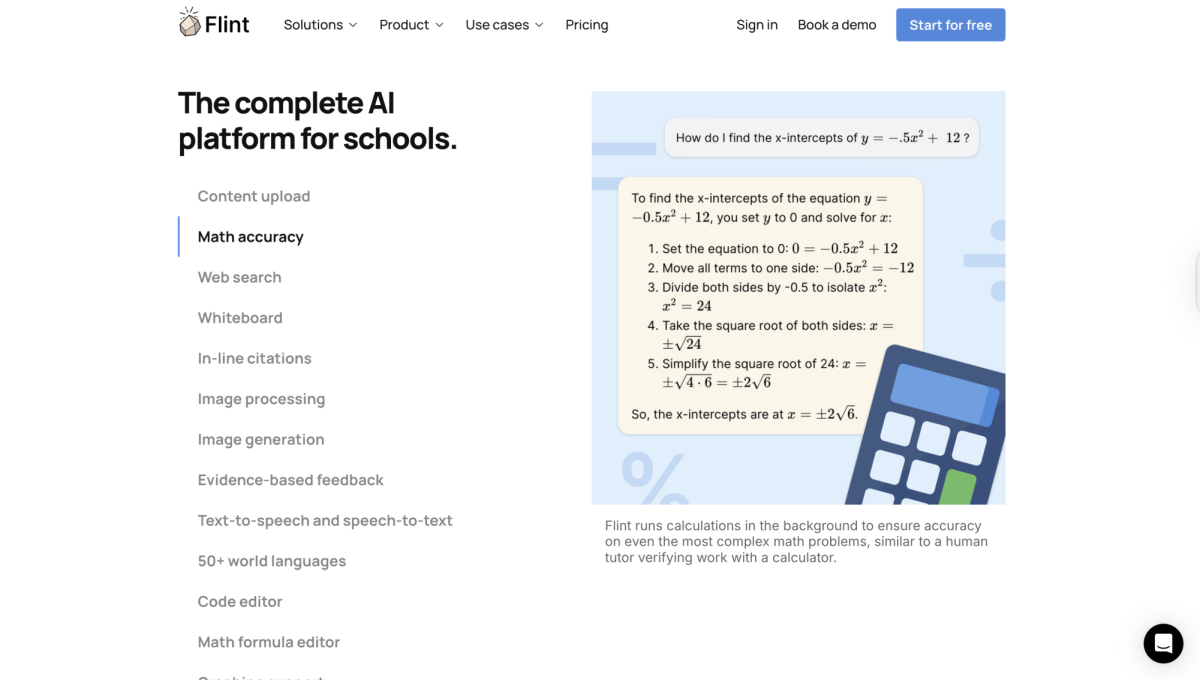

STEM-related departments, like math and computer science, are leaning into the “Go” category. Unlike many humanities classes, where AI is often viewed as a direct violation of the honor code, STEM teachers are exploring AI as a tool to deepen understanding rather than replace effort. Instead of encouraging students to have AI simply solve problems for them, teachers emphasize using AI to dissect complex concepts, generate study material and foster critical thinking (without replacing it).

In Stephen Bates’s PreCalculus classes, students use Flint, an AI chatbot that prides itself on creating a customized learning platform for educators. Bates uses it “almost like a personal tutor,” encouraging students to use it to help them with homework, or to create study sheets. “AI is not going anywhere,” said Bates. “It is our job as a school to teach you how to use it responsibly,…what is right and wrong, and how to identify the misinformation and bias it produces.”

Computer Science Faculty Member Ben Farrar allows AI use in his Object-Oriented Programming class, as long as students cite it and can explain the code they produce. Despite the tool’s potential, Farrar remains cautious about its reliability: “It’s not even just that it’s wrong — it’s confidently wrong,” he said. “That’s what worries me. It makes you believe it, even when it doesn’t know the answer. Students might start trusting it without realizing it has no concept of right or wrong.”

One of Farrar’s students, Levi Drucker Mann ’28, used ChatGPT to help him code a digital “sunset project,” where students had to create a cityscape with moving animations. “[ChatGPT] showed me how to use something called ‘mod,’” Drucker Mann said. “[It] can be a great tool but, at the same time, I think students need to be careful with making sure they’re not taking too much from [it].”

The “Stop, Slow, Go” system ultimately reflects Poly’s broader effort to teach intentional AI use. Dillon noted, “What worries me is that AI does not push back. It will just confirm your ideas. The risk is losing curiosity and critical thinking—and the work gets boring.”

Across subjects, teachers are reimagining what learning looks like in an AI-driven world. “It pushes students to think critically, without simply outsourcing that process,” Dillon added.

This conversation mirrors a national one. According to The New York Times, universities such as Duke and the California State University system now provide students with personal ChatGPT accounts, while Georgetown University’s library even lists an entire page of approved AI research tools. OpenAI has called this the rise of “AI-native universities,” in their sales pitch, but critics caution that overreliance could weaken critical thinking and reinforce bias, according to the New York Times—both concerns Poly’s policy seeks to address.

Hershkovitz cautioned against viewing the policy as final, highlighting broad concerns about AI’s ethical and environmental implications. “AI is an engine of bias,” she said. “Let’s face it, it is programmed by humans, humans who are full of their own biases and faults, literally fill the robot so that it replicates those biases and faults. AI is also environmentally, very, very costly. It is a thirsty robot and it is compromising water resources.”

Bates echoed that sentiment, acknowledging that both the technology and the policy are still works in progress. “We’re building the plane as it is flying,” he said. “The policy today may not be the policy in six months.”

For students, that means digital literacy now includes more than just knowing what AI can do—it means understanding how and why it works, and using it with both creativity and caution.