Financials of a Private School: How Poly Uses its Budget

February 15, 2023

Overview of Budget

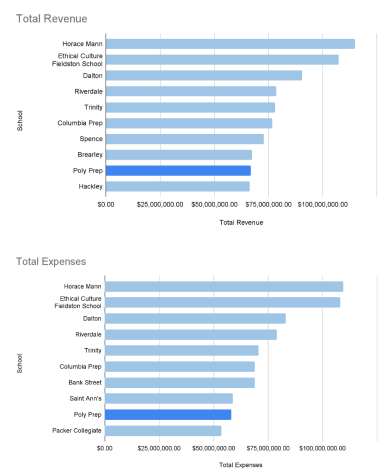

During the 2019-2020 school year, Poly Prep Country Day School spent $58,049,434 to keep the school running, according to the most recent IRS returns, for 1,151 students (these are the most recent returns, as they are still processing returns from April 2020 and later). Where does this money come from? How does the school spend it? How do they decide the budget? This article aims to answer all three of these questions.

Poly’s budget is formed by the Board of Trustees, a group of 23 volunteers, according to Poly’s website. Every one to two months, they meet, according to Head of School Audrius Barzdukas, to maintain “the vision, our school’s identity… Are we becoming what we say we want to become?” They also govern the faculty and staff that create programs, do day-to-day management of the school, and spend Poly’s money by creating a budget. Barzdukas and various other leaders are ex-officios of the board. They attend and participate in meetings but ultimately do not vote on decisions. The Board members and ex-officios organize themselves into committees—examples include finance, auditing, investment, buildings and grounds, and education—in order to split the work of the board among areas of expertise.

According to Barzdukas, Poly uses its revenue of $66,907,657 as stated by the IRS, as a base for its budget during the school year. The budget has five main sources: tuition income ($53,897,394), auxiliary income ($3,401,182), contributions from government sources ($575,465), contributions and donations ($5,107,027), and an approximately $1 million pull from our school’s endowment, a long-term savings account of sorts.

School programming gives a window into how approvals for budgets work at Poly. For example, if an art teacher wanted to purchase tickets to the Met so that their students could do an art study, they would first ask the head of the arts department. The head would then ask their division head, who in this case would be the head of academics. The head of academics would then ask the financial office for approval. Once the financial office approves, the approval then trickles back down to the arts department, which purchases the tickets for the teacher, according to Chief Financial Officer Lynda Casarella.

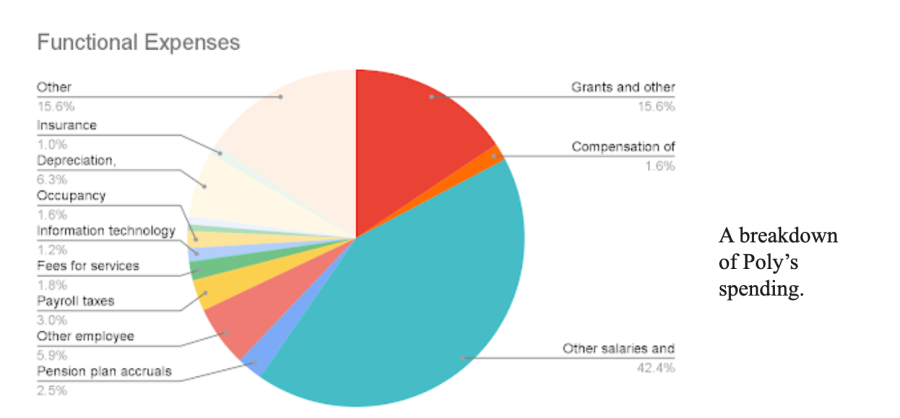

The school has in return five main expenses: salaries, employee benefits, and other kinds of compensation for 768 workers, with about 300 working at Poly year-round ($32,124,786; ~55.34 percent); financial aid for 229 students ($9,072,653; ~15.63 percent); campus maintenance ($1,009,377); legal, accounting, investment, and other kinds of services ($1,629,328); and school programming, which includes busing ($2,714,168), travel ($365,199), food ($1,656,063), books and supplies, sport uniforms, and the like.

An example of the school having to pivot hard in its spending was the pandemic. According to Barzdukas, “During the pandemic we had…extraordinary expenses…for example, testing, we had to [purchase] something like 30,000 COVID tests. The board went into emergency extraordinary sessions where, again, similar to that model…we have to put together the plan. How are we gonna handle the pandemic and present that to the board?”

The main ways the school reinvests in itself—it legally has to due to its non-profit status—are through its endowment and remodeling parts of the school, such as replacing carpets or painting walls; the latter is decided on through a board vote, according to Casarella.

Casarella also said that Poly, like many other private schools in New York, hires external auditors (we spent $87,000 on accounting services) to ingest and verify our books and then output a Form 990, a special tax form for non-profit organizations. Since the school’s various departments all separately manage their own books before sending them to the Financial Office, which then passes them on to the third party, this can make it seem like Poly spends no money on certain categories of expenses, like advertising, when that money is actually being lumped together into the “all other expenses” category. Once the auditors complete the Form 990, the Board’s Finance Committee and Audit Committees review it, and with their approval, is signed off by Casarella and sent to the IRS for public availability.

The Role of CFO

As a chief financial officer, Casarella oversees most of Poly’s finances. Having joined Poly in December of 2015 as the associate director of Summer Programs and External Learning, she rose up to become the controller of the Business Office in 2019 and became CFO in 2021 after taking an interim position in 2020, according to her staff page on the Poly website. Answering directly to the Head of School, her day-to-day consists of overseeing the Business Office, managing payroll for approximately 300 of Poly’s employees, ensures that vendors that Poly hires for snow removal and construction are paid properly, handling legal matters like contracts and workplace injuries, and generally balancing the checkbook, according to Casarella. In terms of her relations with the Board of Trustees, the Financial Officer acts as a liaison between the Board and faculty, and she is a member of the Finance and Investment Committees.

Casarella said her largest concern as of late has been inflation, which is a tightrope for the school to navigate: “Inflation affects the school in that inflation affects everything. The fixed costs of running the school (food, electricity, books, insurance etc.) have all gone up due to inflation. Even though those costs have increased, we still have to pay for them, which means that we ask families to contribute more in their giving and increase the tuition as well.” The problem cannot be solved simply by raising tuition, as even raising it by five percent may prevent families from being able to afford the costs of attending, and the amount of money earned wouldn’t be enough to counter the effects of inflation.

However, Casarella said she takes pride in her work even with these challenges. In her words, “Being a CFO is really the steward of the school’s financial and physical assets. My feelings are that I absolutely love my job. I love knowing that what I do day-to-day has an impact on the school now and will have an impact on the future of the school.”