In the midst of heightened political polarization, the prevalence of cancel culture, and a looming presidential election, the Poly Prep community is grappling with how to foster a healthy environment for political discourse. The fact that Poly community members hold a vast variety of political viewpoints exacerbates the difficulty of having these conversations on Poly’s campus.

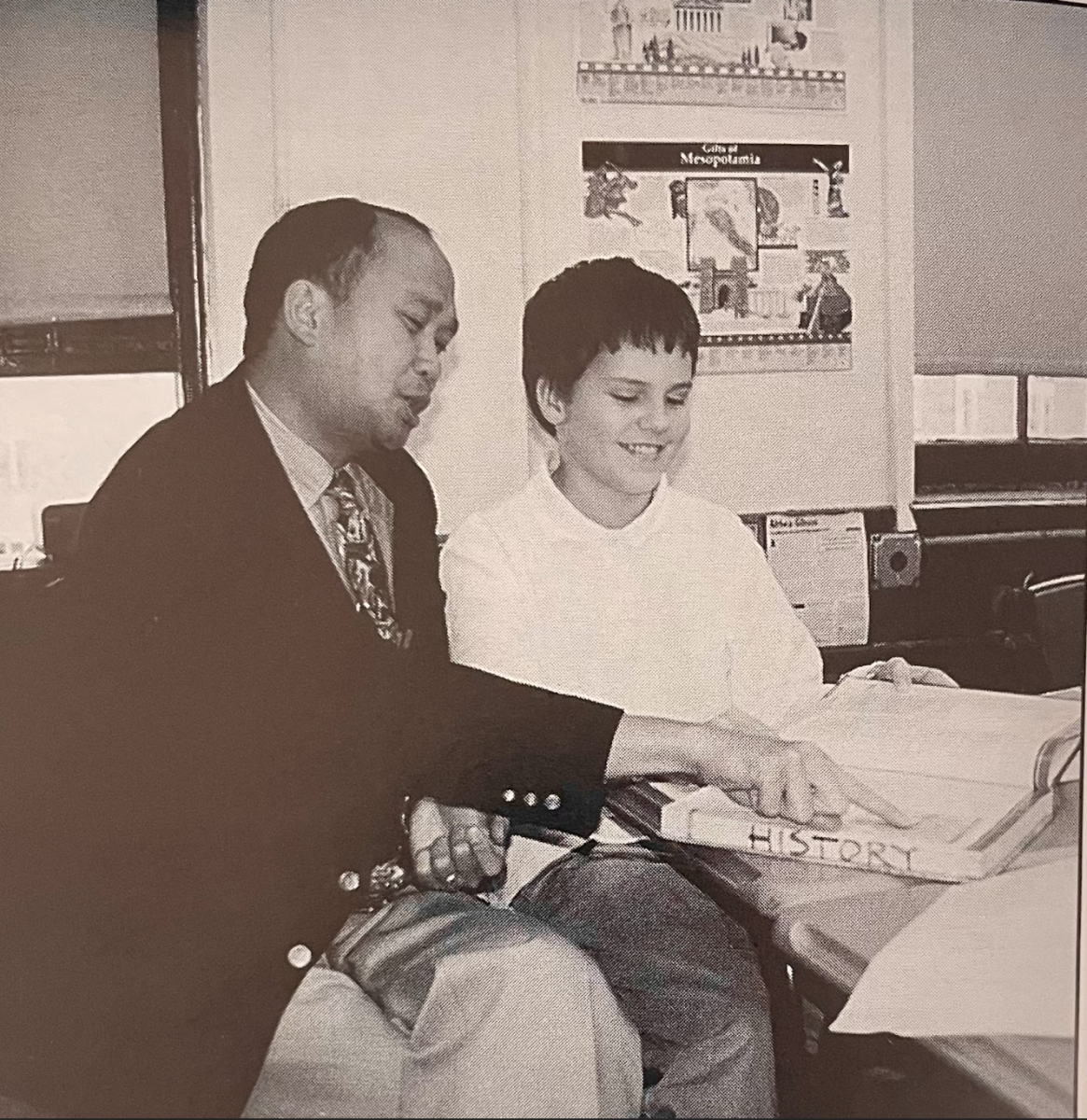

Historically, Poly has been perceived as a liberal institution, being founded in 1854 as a progressive educational establishment. History teacher A.J. Blandford explained how “although the school was following a liberal education system, The Brooklyn Eagle newspaper labeled Poly as a Whig institution around the same time.” In 19th-century American politics, the Whig Party was considered very conservative. “Although the school was following a liberal pathway, the students were primarily conservative from elite Brooklyn families,” said Blandford.

Fast-forward to 2024. According to “Fast Facts” on Poly’s website, Poly students come from all over the city. A study titled “Party Affiliation in New York” by the Pew Research Center shows that more than half of New York State residents identify as Democrats, with the Democratic candidate winning New York votes 86 percent of the time.

Junior Mila Taendler has attended Brooklyn private schools her entire life. “I have definitely noticed trends of primarily liberal and democratic families with whom I go to school,” said Taendler. “At Poly, although the school doesn’t have a political party the administration ‘promotes,’ I definitely noticed that the student body is primarily liberal.”

A recent incident sheds light on the complexities of expressing diverse viewpoints within the community. Former Poly student Lukas Archer — who now attends Avon Old Farms to play lacrosse — recounted an incident from his sophomore year when he faced backlash for wearing a shirt with an NYPD flag. “At lunch, students took photos of my shirt and shared them on social media, labeling me as ‘conservative’ and ‘Republican,'” said Archer. Before the shirt incident, Archer had never expressed his political views to anyone outside his inner circle. “After this, I was hesitant ever to express my political views at Poly just because I didn’t want to deal with it again. It felt like I was being canceled.”

Americans for Prosperity, a conservative political advocacy group, found that one in four Americans fear that cancellation culture could risk their education or social life. This keeps those from expressing their political opinions because they fear their community will not accept them and jeopardize their well-being.

Assistant Head of School, Academics, Michal Hershkovitz, acknowledged the challenges of fostering genuine political engagement amidst the deluge of misinformation and fear of cancellation. “There’s a lot of misinformation, disinformation, and outright lying on social media,” said Hershkovitz. “I wish more students could ask real questions, state their values, and test their positions. But the fear of canceling online hampers this.”

A conservative Poly student from Brooklyn shared, “I feel like people in my generation often equate the term ‘conservatism’ with values such as racism or homophobia. I know my values, which could not be farther from those, and I understand that the way some students perceive Republicans doesn’t reflect who I am.” As a result, this student chooses to keep their political views private. “It’s just not worth the hassle. I know who I can trust, but the stereotypes that people generate are exhausting.”

This student asked to be kept anonymous. Out of the 10 conservative students who were asked to go on record, not a single one felt comfortable doing so because they felt that they would receive judgment from the Poly community for being openly conservative.

Junior Tallulah Glancy is openly liberal, yet she feels the exact same way about expressing her political views as this student. “Today everyone is so sensitive and dramatic when it comes to politics. With kids my age, no one really knows what they are talking about, and it often just leads to arguments and generalizations.” Glancy keeps her views to herself to avoid conflict and conversations that she finds “unproductive and inefficient, whether with a Republican or Democrat.”

During the interview, Hershkovitz posed a critical question: “So what do we do? How can we marshal the virtues of political diversity at Poly to help us understand each other better in the world?”

To address this challenge, faculty and administrators developed a comprehensive plan for handling election discussions on campus.

In collaboration with the History Department, election season will include a variety of forums, town halls, and moderated political debates. These events will be times when students can come together and have open conversations with the goal of understanding each other’s views. “Students with political ideologies on the far right or left often have overlapping beliefs,” said Jared Winston, Head of Student Life at Poly. “We should not be confused by the binary idea of political ideologies. There’s always common ground to be found.”

According to a study by Taylor and Francis, a company that publishes academic journals and books, only three percent of politically engaged internet users attend in-person political debates. This leaves 97 percent of users debating topics online without real contact.

Hershkovitz wants to motivate students to have these discussions in person so they carry the habit with them beyond Poly. “The interchange of ideas, the exploration of differences, the honest sharing of controversial thoughts, provocative questions,” said Hershkovitz, “is where real, productive conversations and debate are made. That is how we will grow and come together as a community.”